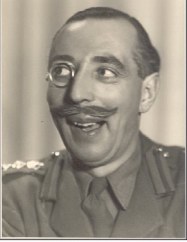

Francis Carl Willmott in the role of The Duke of Ayr and Stirling in Terence Rattigan's While the Sun Shines

A special welcome to members of the Air Formation Signal Regiments' Association, in the hope that they will find interest and entertainment in my father's account of his WW2 career in the Signals ...

NB: This is a very long document!

THE WARTIME MEMORIES

of

Francis Carl Willmott

as explained to his Grandchildren.

INTRODUCTION

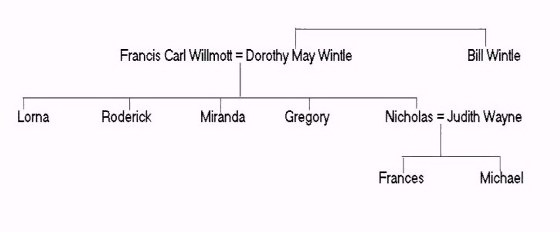

In the spring of 1996 my daughter, Frances, came home from school with a history homework task. She was to ask an older member of her family for a few memories of the Second World War. Her Grandfather was telephoned and was happy to oblige. The episode that he wrote so intrigued the children that they asked for more. Over the next year, few weeks passed without a substantial portion of wartime autobiography being enclosed with the weekly letter of family news.

I have now gathered these accounts together and present them in sequence.

Considering that Dad typed these memories with very limited eyesight, episodically, and with no opportunity to check names, places and dates; the amount of editing required has been slight. I have corrected some typing errors and have deleted one or two sentences that repeat information supplied in a previous section. There are some references to photographs, programmes and books that were originally enclosed with the letters. These were subsequently returned to West Witton, but in every case Dad explains their significance in such detail that their absence is not critical.

One or two editorial additions, enclosed in square brackets [ ], have been added following telephone conversations with Dad over the past few weeks. They clarify or expand certain passages. Sections in italics are abstracted from the regular weekly correspondence that accompanied the memoirs. To avoid any risk of giving offence, however slight, a few personal names have been deleted.

Principally for the benefit of non-family members, I have added some explanatory notes. These also provide occasional extra information.

Nicholas Willmott. December 2000

***

Sunday May 23 1996School in the Summer of 1939 was far from normal. Air-raid shelters were dug and built in the playing field to be followed by regular air-raid drill. Gas masks were issued and regularly tested.

Teachers were exempted from military service and given training in emergency measures that would come into force at the outbreak of War. We were given official badges and authority to visit all houses to make a register of all spare accommodation that could be used to house evacuees. We were called Enumerators and had the authority of the Police to back us. I also enrolled as an Air-raid warden and started training. For this I had to ride a bike and Grandma (note 1) had to teach me to ride. We used to get up in the early hours and go up and down the road when no-one else was up and about. Everybody in Cambridge rode a bike and they were hard to get at that critical time. I could only get a lady’s model, but this was easier to mount and fall off. A warden’s post was built on a road island not far from our house, but I had to use the bike to go round and rouse others in case of emergency. My bike had a most peculiar sound in motion, so when War eventually came, Grandma always knew when there was an emergency. That was in the future, for the moment there was other training to be done, such as going through various gas chambers and recognising the gases, together with applying first aid.

When war finally came in September, we teachers all became Billeting Officers. By this time I had four different identity cards. As enumerators we had recorded householders’ preferences as to sex and age of prospective evacuees. In the event these were useless; in our part of Cambridge we only had Polish mothers with babies in arms and huge boys from a North London Technical College, who had to share our School building for lessons. On that first day of War I walked the streets with a six-foot pupil whom nobody wanted. At 10 p.m. I returned with him to the billeting office where no-one remained except the young infants’ teacher who was to lock up. My tall foot-sore boy was in tears. I would have taken him back home but Rod was only three weeks old, and we already had two evacuated teachers staying with us. The young teacher took our rejected evacuee back to her own flat. That was the beginning of a story that must be kept for a later edition.

July 7 1996

I had intended to go through the years of the Second World War telling stories in the order that they occurred. However your interest in the unwelcome evacuee prompts me to complete his story as far as I know it.

THE UNWELCOME EVACUEE

You may remember that I spent the first day of war in 1939 taking evacuees to their Cambridge hosts. You will also recall that I had one very large London schoolboy who no-one wanted. He walked with me round the Cambridge streets and was finally taken in by a young lady teacher who took him home to her small flat. In the days that followed there were air-raid alarms in Cambridge, but none in London. Quite a lot of young children and mothers went back, believing that they were better off in London. Our own Coleridge School was being shared by the North-West London Technical College, who did not go back as the School buildings were so good.

Nearly every day I saw the young man who had walked so many streets with me. In the early morning he could be seen with the teacher who gave him shelter. He appeared very happy as he carried her books to the Blinco Grove School, where Lorna later became a pupil. There were wagging tongues from neighbours, but they couldn’t say much, as they had been unwilling to take the boy themselves.

As time went on the progress of War gave us other things to think about. I was in the Royal Signals for five years, until peace was signed at Lüneburg, and I was transferred there as an Education Officer. There was no more fighting to be done, but the British Army was responsible for keeping the peace and occasionally I had to sit up all night as duty officer. In the office below was a soldier also on duty as a clerk, keeping records and answering the telephone.

One night when I was on duty, the clerk came up and asked me whether I would like a cup of tea. He offered to bring it up, but I liked company and I said I would go down and join him.

As he poured out the tea he said, “You don’t remember me do you Captain Willmott?”

I didn’t recognise him, so he added, “I am the boy who walked the streets of Cambridge with you on the first day of the War.”

We stayed talking for the rest of our night’s duty. I cannot go into all the details, but this young man was drafted into the Army not long after leaving School. He had been wounded in the Rhine (note 2) crossing and was back on light duties.

Sadly, he had to tell me that all the rest of his family had been killed in an air raid. Being wounded, the only home to which he could go on sick leave was the lady teacher’s flat in Cambridge. Tears came again to his eyes when he said that the teacher was the only one he had left in the world.

I wish I could tell you the end of this story, but we left Cambridge before this young man was discharged from the Army. I have a feeling that he married the teacher. He was in his early twenties and she was not then thirty, so the age difference was not great. We hope they lived happily together for a very long time.

PHONEY WAR

The first weeks of the War were quite dull. This is going to be rather boring after the boy’s story that I told you last time. Everybody expected air-raids that never came and many of the evacuees went back to London. Coleridge Boys School, Cambridge, was new in 1937 and so the N.W. London Technical was quite glad to be there. The workshops and science rooms were better than theirs back home. They got on quite well with our boys, although they were older. At that time our boys entered at age eleven and left at fifteen; the Londoners were aged thirteen to eighteen.

We thought that we should only be working half days, but it didn’t work out like that. We would start at nine in the morning and use the classrooms until 1 p.m., when we had our school dinner. The London boys had their dinners at noon and classes from one until five p.m. In the morning they had the use of the Hall, the Gymnasium and the Playing Field. We used these spaces in the afternoon. From this you may work out that our school day was eight hours long; in peace time it had been just five hours. This was not all.

In the evenings the London teachers arranged clubs and other things at school so that the boys would not be a nuisance to their hosts and hostesses. Our workshops were used to make things useful for the War effort. Not many people know about this. The Pye Radio works had gone over to the making of Radar equipment for the armed forces. With our up-to-date metal lathes and shaping machines we were able to help. Your Daddy will be able to tell you more about Asdic detectors. They were used by the Navy to detect German submarines. Submarines were used not only to sink our War vessels but, more particularly, to starve us out by sinking the merchant ships bringing us food. In our workshops we were able to make the condenser plates that were vital parts of these Asdic detectors. The older boys from our two Schools did this work in the evenings. This was not the only way in which school children were able to help. I remember that we made collections of things like silver paper wrappings that were used for salvage. In the First World War, when I was in Infants School, we were asked to collect horse chestnuts (conkers) and take them to school. These were sent to factories and used in the making of explosives. In the Second World War, as I have already said, the Germans again tried to stop food getting to us. There were no bananas and very few oranges. To take their place school-children were asked to collect rose-hips. When I went back to Cambridge after the War, Chivers jam factory was still collecting rose-hips brought in by the Schools, and from these they manufactured rose-hip syrup for feeding to babies in place of orange juice. I think that it is still being sold today as a source of vitamin C.

I am sorry Frances, but all these memories are about boys and I haven’t mentioned the girls at all. I must point out that ours was a boys school. The girls were in an adjoining building, but they could not have been more separate. Miss Howlett, the Head, thought it was her duty to keep her girls safe from the dreadful boys next door. This defence was made even more necessary by the invasion of huge louts from London. With a double school population working from nine in the morning till nine at night, we had no time to think about young ladies for whom the evacuation had made no difference of time-table.

For my own part, I also had my air-raid warden duties, with occasional nights to be spent at the telephone in the nearby Wardens’ Post. Although there were no raids we occasionally had a red alert which meant that Grandma would hear my cranky bike as I cycled round to wake the other wardens. We also had training sessions when we were taken into various gas chambers, so that we should know what the experience was like. We also did practice with stirrup pumps with which every household was supplied for fire-fighting purposes. I cannot remember whether Lorna was supplied with a Mickey Mouse gas-mask, which were issued to young children who might be frightened by the ordinary type. Certainly Rod had a baby’s gas-protector, into which the whole body was comfortably placed.

At the time there was plenty to do and think about, but the War still seemed far away and an uneasy peace loomed over all.

Then came the awful reality. In late May, 1940, the Germans swept through Belgium, Holland and Luxemburg, and the French were conquered. The remaining Allied Armies were driven to the Channel ports and, miraculously, most of them were rescued from Dunkirk. Hundreds of boats of all kinds were used and most got away in spite of continuous shelling and bombing. Many of the soldiers came from the coast by direct train to Cambridge. They were billeted for a short time in the houses from which the evacuees had gone back to London. We had three soldiers at 1, Perne Road. They were tired, unwashed and hungry. For three days they did little but eat and sleep, after a good bath.

A new chapter in the War was opening. Schoolmasters of my age would shortly be called to arms, so I volunteered while there was still some choice in the matter. I was medically examined and passed A.1. This meant that I was too fit for the Army Education Corps. I was told that I would be suitable for training in the Royal Signals. In September 1940 I was sent a rail warrant and instructed to report to the Signals Training Depot at Tilehurst Road, Reading. For the time being my civilian days were over.

August 4 1996

Dear Frances and Michael,

... As you are now so grown up, I think I ought to point out that my true stories about the War may give you a wrong impression. Some of my adventures were quite funny, but I had an easy time. I never had to fire a shot and was never bombed or shot at.

... I didn’t want you to get a wrong impression of life in the Forces during War. We have other friends who spent so much dreadful time in Japanese P.O.W. camps. I was very lucky.

ACTION STATIONS

Almost exactly a year after walking the streets of Cambridge with evacuees, I was in Army uniform. One of my fellow teachers agreed to drive Grandma, Lorna and Rod to your great-grandparents at Old Street Farm in Gloucestershire. This was a happy place for them to be. Our house at 1, Perne Road, Cambridge was sub-let, furnished.

It must have been a very early special train in which I left Cambridge on my way to Reading. It may have been a special, as all the passengers were either in uniform, or on their way to it. Air raids were raging over London and people were sleeping in all the underground stations as we crossed from Kings Cross to Paddington. We were told that the night’s raids had been light and that our train to Reading and beyond would leave as planned.

When I arrived at Ticehurst it was still early and it was to be a busy day. In no time at all I took off my civilian clothes and was kitted out with uniform and all accessories.

I ceased to be Mr. F.C. Willmott, Nat. Reg. No. T.A.B. 145, and became Signalman Willmott, F.C. No.2595790. I had a few days to qualify as a tradesman. As a schoolmaster I was in the communication business. I was merely transferring to another branch of the same business. There were lots of other schoolmasters engaged in the same skills adjustment.

Most trades in the Royal Corps of Signals required a lot of training and skill. I couldn’t see how we should be able to do this training in a few days. However, we learned that we were to be trained for an A.A. unit (note 3), where the requirement was for switchboard and telephone operators - listed as Grade “D” in the list of payment rates. It was more difficult than you might imagine. In the days before automatic dialling you lifted the telephone receiver and called the switchboard operator who then had to call the number you required and made the connection. At that time all Army connections relied on this use of a switchboard operator. There might be as many as a hundred lines connected to such a board. You wore head-phones and sat down in front of a hundred plugs, or jacks as they were called. Above these was a board with a hundred plug holes with light bulbs underneath. When a bulb lit up it meant that number was calling, so you had to plug into the hole above and answer according to an established procedure. Using another plug you then had to call the number required by inserting it in the right hole and ringing by turning a handle in front of your switchboard. If you had a satisfactory answer then you used the plugs to connect the two subscribers. This may sound simple, but at busy times several callers would be calling at the same time. You also had to make certain that the call was proceeding satisfactorily, and break it down when finished. High-ranking officers and urgent calls had to be given priority. Failure to observe priorities could lead to all sorts of trouble.

Learning all this, and more, took up most of the time during those few days, but we had to pretend to be soldiers as well.

Our training as fighting men will be found overleaf. Turn with care!

..........................................

.........................................

At the end of my first day as a soldier I was surprised to find that I was listed for guard duty on the very first night.

We were not exactly in the front line, but we had to keep up appearances. Our armament was not heavy. The Home Guard had to drill with broom-sticks, but we had a real Ross Rifle, (Mark 2), carefully preserved from the Boer Wars (note 4). I was shown how to use it, in theory. We only had one bullet, which we signed for on taking up duty. We kept this in our pocket in case of emergency.

I shall not forget that first night of duty. There was a heavy raid over London, only twenty-odd miles away. It was a tremendous sight, with search-lights, A.A. fire and air dog-fights lighting up the sky; there was a constant glow as the fires of London came from below. Every now and again a ping on the top of my tin-hat made me think that shrapnel was falling all around. I thought I could see German parachutists coming down above the trees. The light of the following morning revealed that the falling armaments were over-ripe conkers falling from trees in the drive.

So ended my first day of active service.

WESTWARD HO

You will remember that the second year of the War opened with Grandma, Lorna and Rod off to Old Street Farm in West Gloucestershire. Meanwhile I had gone South and expected to remain in the London area after training.

By this time the German air-raids had extended to other parts of the country, particularly the south coast towns.

My job was to be in Anti-Aircraft Gun Operation Rooms. For me this meant Bristol, Gloucester and Cardiff for most of the next two years. At each place it was fairly easy for me to get to Old Street Farm, so I still managed to see quite a bit of the family.

You will remember that I was trained as a switch-board operator. Although we all served turns on our very big and busy board, it only occupied one man at a time. Our main duties were in the G.O.R. itself. These rooms varied in lay-out and size, but the main features were the same. In the centre was a very large table marked out as an ordnance survey map of the south of England. We all stood round wearing head-phones through which we had information about air-raids and we plotted these on the map. If I remember rightly German planes were indicated by swastikas and the British by red, white and blue circles. In a circle above us on a platform sat the officers, also wearing headphones and a breast microphone to speak to the gun-sites. We, who mapped what was going on, listened to information that came from R.A.F. stations, Search-light batteries, Barrage-balloon controls, air raid wardens, Fire services, the Police and, especially, Observer Corps posts. The officers above relayed the information to gun positions where the final decisions about firing had to be made.

When the figures of German planes brought down are studied, it can be seen that a very small proportion were brought down by A.A. fire. In those days there were no ground-to-air rockets or missiles of that accuracy. The guns fired shells to explode at the estimated height, and so the targeting was not accurate. They were not allowed to fire when our own planes were in the area and they had to be aware of barrage balloons and the effects of fall-out. In fact the guns more frequently put up a barrage to keep the enemy out, rather than bringing them down.

Although we had lived for such a large proportion of our lives in Bristol, I cannot remember much of my posting there. I cannot even recall where the G.O.R. was situated. It soon became apparent that the situation there was too vulnerable and it was decided to move to Gloucester.

In contrast to Bristol, I remember this site very well. We were in Prince’s Hall, a dancing salon in pre-war days. It was right in the centre of Gloucester, with the front doors opening on to a main street and back door straight on to the cattle market. Our beds occupied the whole of the ballroom floor, while downstairs were toilets, a kitchen, refreshment room, and a spacious conference room, ideally suited to be a G.O.R. As we worked mainly at night, the noise from the street and the market was not conducive to sleep, but we became accustomed to this. Even when not on official leave I could get a lift to Old Street Farm and family when on rest for 24 hours. I had some strange lifts; once on a hearse and once in a load of stinking cattle skins from the abattoir in the market.

This was a fairly happy state of affairs that was too good to last. Intelligence reports suggested that the Nazi planes were likely to extend the target area to include Gloucester and Cheltenham. Our central G.O.R., also very near to the Railway Station, was much too vulnerable. We were moved to Badgeworth Court, an empty country house halfway between the two large towns, and well away from even a village. This was very comfortable, but not so convenient to hitch-hike “home”.

At this time I was recommended for officer training and had to attend a War Officer Selection Board. There were lots of interviews and some quite hard tests. In one of these you had to lie face down on the Gym floor with a paper and pencil and an exercise book. In this position you had to work out arithmetic problems while N.C.O.s kicked footballs over our heads. Surprisingly, I passed and was promoted to the rank of Lance-Corporal (acting-unpaid).

Life was so safe and easy at Badgeworth that it was decided to replace us all by women of the A.T.S. (note5).

As I was destined for officer cadet training, I was not posted away with the rest of the men. The Sergeant in charge also had a temporary reprieve and together we had to introduce the girls to their duties. They had been well trained and were probably better at this work than were the men. In any case local air activity had lessened very considerably. Supervision of Bristol had been transferred to Cardiff, together with that for the whole of Wales and the border area. There it was still a man’s job. Consequently I was sent to Cardiff to work until posting to O.C.T.U. (note 6).

That was the move that took me to Pen-y-lan Court (note 7). Is it still there?

WELSH RAREBIT

From my point of view war-time Cardiff was very different from Bristol, Gloucester and Badgeworth. In those places we were a very small detachment of about thirty under one sergeant. We never saw an officer, except in the G.O.R.

At Pen-y-lan Court the corridors were crowded with military personnel. In the streets there were many soldiers, sailors, airmen and merchant seamen. There were also quite a lot of women in uniform - including the civilian W.V.S. (note 8).

It seemed as if Cardiff had been long preparing for this influx of services. They must have been saving up in the hill-sides and valleys. Every main street had a Forces canteen with home-made Welsh cakes. Every chapel was crowded on Sunday evening and refreshments were served afterwards by an army of willing ladies. The singing was very good and a long sermon could be borne with the prospect of joys to follow. There was no silver in the collection, but dishes of very heavy copper.

I cannot remember whether I did any operation room duty at Cardiff. The fact is that there were so many of us waiting to be posted that there were many bodies to spare. I did, however, train to be a cipher clerk.

The highest grade for signalman was that of morse operator. To pass for this rating a very high speed of reading and operating was required and the tradesman usually took down the messages in short-hand. Such operators also knew secret codes and they were entrusted with highly confidential secret messages. By 1941 increasing use was being made of the teleprinter. I had to learn how to operate one of these. The most difficult thing was to learn a mathematical formula which had to be learnt without being written down; because it was so highly secret. According to this formula the letters had to be arranged to make up the code for the day in question. Having qualified, I used to go on night duty taking practice messages and being ready for real traffic. It meant sitting up in front of a screen, exactly like the one that now shows the football results coming through on Saturday television. Not all the messages would be for me, but I had to keep awake and there was no means for asking questions. The practice messages were never checked and had to be destroyed before going off duty. There were some routine messages that were identified by a prefix and they were delivered the following morning. It was very rare to have a real secret message, identified by having no prefix.

I can only remember having one such “real” secret signal.

I cannot remember exactly the text of the signal, but it was something like:-

“Cpl. Evans, HT is available to play at Cardiff Arms Park on Saturday (date)”.

It was addressed to Capt. J. Peterson (note 10).

Capt. Jack Peterson was a formidable national figure. At that time he was Heavyweight Boxing Champion of Britain, and many other spheres. The prospect of waking him up in the middle of the night was not attractive.

There was a despatch rider on hand to take despatches when required, but it didn’t require a motor-cyclist to reach an officer who was sleeping in the same building. He occupied a suite of rooms as officer in charge of Combined Services Recreation.

Using all my authority as a Lance-Corporal (acting unpaid), I woke Jack Peterson’s batman and directed him to wake his officer and deliver the signal.

With a torrent of Celtic curses ringing in my ears I dashed back to my teleprinter screen and awaited the wrath to come. Strangely enough it didn’t. The next day I hurried past Jack Peterson in the corridor and he actually smiled. Perhaps the message was really important. After all, the Germans didn’t invade Wales. Or perhaps it underlined the truth that, to a Welshman, Cardiff Arms Park is a more important battlefield than Normandy, Waterloo, or even the playing fields of Eton.

From Cardiff it wasn’t very easy to hitch-hike to Old Street Farm, but I had regular 48 hour passes. Showing these at Cardiff railway station I could get very cheap railway warrants to Lydney Junction. As I worked mainly at night, my passes went from evening to evening. Consequently I used to arrive at Lydney very late and had a long walk in the black-out to Old Street Farm. I had one or two frightening experiences and twice fell into a very wet ditch. I was always relieved when I saw the outline of the farm house on the night sky-line. Old Bob, the dog, would usually be on guard and would bark on my approach. However, he always recognised my voice and met me wagging his tail. It was this lovely dog that helped Uncle Rod to walk. Rod would put his arms round the dog’s neck as it walked slowly round.

During the day I was able to get a train back from Awre Junction, a small station much nearer to Blakeney. Passing an isolated cottage, I was surprised to see an official warning on the gate:- “Danger - Unexploded Bomb”. As I approached the house, a man came running out to ask me when I was going to remove “this xxxx thing”. As I was in uniform, he thought I must be one of the bomb disposal squad who had made the weapon safe and had promised to come back and remove it. His chief worry was that it had ruined his onion bed. It seemed of little concern that he, his family and the house had narrowly escaped complete destruction.

When I got back to Cardiff I found that this bomb had been carefully mapped, following a raid only four nights earlier. A stick of five had been dropped; two in the river, two on open ground where they had exploded harmlessly, and the one in the garden that had not exploded. It was the deep digging in the onion bed that had saved the house and all who lived there. These were percussion fused bombs that only exploded when the nose-cap met a solid resistance. In this case the projectile had penetrated some thirty feet into the soft earth until it had no more momentum

Although the bombers had navigational aids, they still flew with guidance from what could be seen below. The Thames and the Severn were great pathfinders, especially on moonlit nights. When frustrated in their raids they would fly back along the same route, unloading their bombs along the banks of the river.

My days at Cardiff were numbered, and so came the posting to O.C.T.U.

The next year was to be the most strenuous of my Army career. I don’t think I have ever had to work so hard, both physically and mentally.

ON THE ROAD

When I joined the Army in 1940, The German invasion was expected and all our preparations were for defence. When I left Cardiff the air battle was being won and the War Department was preparing for attack in different parts of the world. Defences were being manned by older age groups and the Home Guard. Similarly, women had taken over many essential roles.

I went to a pre-O.C.T.U. at Wrotham in Kent. Here we were put on a production line and subjected to a factory-like routine. At the age of thirty plus, I was one of the oldest pieces of raw material. There were hundreds of us and we were housed on a newly constructed purpose-built site. We were rigorously organised with no time or space wasted. The first parade was at 7 a.m., and there was a full programme until Lights Out at 10 p.m. We were housed in great long barrack rooms where we slept in bunk beds. Feeding was in a very long Mess Room of the same basic design, as was also the lavatory room with seats along each wall. I cannot remember a lecture hall and I think that all instruction was out of doors. There was a long ablution, or washing room, where we elbowed one another to wash in the morning. There were showers all down the other side.

Since my first night, at Reading, I had not handled a rifle. Now I was issued with a new Lee-Enfield as my constant companion. I marched with it, I drilled with it, I named all its parts, I cleaned it every day and I slept with it. But I did not fire it. We had one case of dummy bullets that we used for practice loading.

Your daddy may have copies of two poems by Henry Reed (note 11) that tell exactly what some of our training was like. They are called “Naming of Parts” and “Judging Distances”.

Every morning, besides a roll call and parade, we had to stand by our beds for a kit inspection. For this there was a set arrangement of every item and the rifle was inspected by a sergeant squinting down the barrel. To prepare for this we had to use a long pull-through, - an oiled scrap of flannel attached to a long draw string. I remember one fellow cadet who had failed to do this one day when a moth took refuge in the barrel overnight. He was in serious trouble.

When I was allocated my bunk, I noticed that the man above me was called Tanner (note12); he was one before me on the alphabetical list. It was some three days later that I learned that his first name was Haydn and that he was the famous Welsh international rugby player. He was a national hero in the Cardiff I had just left. He was to be my closest Army companion for the next eighteen months. He called me “Willie Bach”, which became “Bill” or “Billie” to others later.

We were only at Wrotham for some four weeks or so, but it seemed much longer. The purpose was to give us a crash course in all the essential officer duties that would be common to all Regiments and specialist units. These included Drill, military law, first aid, digging latrines, judging distances, map-reading, and conducting funerals. The list is much longer and all the details are in a Field Service Pocket Book (note 13) somewhere in our library. Oh dear! I’ve left out setting up a field kitchen, one of the most important duties.

Beyond all this training enshrined in the Field Service Pocket Book, the most important feature of our cadet training was the driving and care of Service Transport. We had one week on four wheels and one on two. At the end of each week was a driving and maintenance test that had to be passed.

It may surprise you to know that there was no man in my squad of thirty that had ever driven a car. There must have been some in the other squads who had driven private cars, but military transport was more difficult to handle. We did all our driving practice in 15 cwt. and 3 ton trucks. They were heavy to handle and all gear changing had to be done by double de-clutching. There were no trafficators (note 14) and all signals had to be given by hand. The wind-screen wipers had to be operated by hand and the self-starters operated only occasionally. In the early morning we always had to start by using a vicious starting handle. Often the engine kicked back and dealt a savage blow through the handle. Most of the vehicles were open and any covers could be easily removed. There was no system of locking, so every vehicle had to be immobilised on leaving unattended. The usual method was to remove the rotor arm. We also had to learn to do daily maintenance and to conduct an officers’ inspection. This meant donning overalls and crawling underneath the vehicle. I passed all these tests without much difficulty.

The same could not be said of the motor-cycle course which came in the following week. Again we were trained on very heavy models, which were more powerful than I was. I did reasonably well on the road where we always moved at a modest rate in convoy. But the final test was on a battle course with shell holes and bomb craters and fire crackers thrown over our heads.

I emerged from this ordeal covered with bruises. We had to ride in and out of a bomb crater. Three times I tried this and each time I finished at the bottom of the crater under the machine. On the last occasion I wheeled my bike out and re-mounted. Apparently this desperate move was my salvation and I was deemed to have passed ...

Sadly I was a modest smoker at that time and my cigarette case was squashed and flattened into one piece of metal.

So ended our pre-OCTU, and we moved to greater terrors at Catterick.

Oct. 11 1996

Dear Frances and Michael,

... As I have now had a letter from, and a talk with, Haydn Tanner, I thought I would tell you a little more about him in this week’s story.

CATTERICK CAPERS

At the Signals O.C.T.U. we had to work very hard and we were expected to play hard. As I remember, parades started at 7 a.m. and ended at 5 p.m. The evenings were free and there were entertainments and canteens. However, it was something like school; there was no homework, but there were exams to be prepared for and rules to be learned, as well as rifle cleaning, boot and button polishing and other personal tasks. For example, we had a sewing kit, called a “Housewife”, and we were expected to do all our darning and button sewing.

In the evenings we also did games training, play rehearsals and band practices etc.

I had not played rugby for more than eight years, but we all had to play some game on Saturday afternoons and rugby had to be my choice. Most football players played soccer so we had barely enough rugger players to make up a team. However, we did have this International star, Haydn Tanner, who won most of our games single-handed. He subjected us to rigorous practice in the evenings. My ears were nearly screwed off as I was subjected to scrum practice in the second row. That is the position where you have to insert your head between two boney backsides, while being pushed and held by a sharp shoulder in the rear. In the gym we had a scrummage machine to push against. I became inured to this form of torture and I learnt to get by with minimum suffering. But worse was to follow. On the eve of our needle match against the Artillery, our full-back, another Welshman, suffered an injury and could not play. As I was a friend of Haydn at the time and, consequently, ready to hand, I was designated Lord High Substitute. In the half darkness I was taken out to practise catching the ball and kicking to touch. I knew the position in theory but had never played there before. Every moment that could be spared before the match, Haydn was at my side feeding me with technical advice. Finally he assured me that he would always try to get behind me to sweep up. On the great day I think I did quite well. At half-time Haydn was kind enough to say so.

Not long before the final whistle came disaster. We were winning by a narrow margin when the opposing forwards, with the ball at their feet, came rushing towards our line. I knew exactly what to do; I had to dive and fall on the ball. Instinctively I threw myself at the enemy feet but I failed to cover my head. Consequently I suffered multiple injuries, including a broken nose. I have never played again since that day, but I did prevent a score and our team won. I was escorted to the hospital in some triumph.

There was a choice of team games for Saturday afternoon, but no such variety for Wednesdays. For that afternoon it was always a cross-country run. I cannot remember the exact distance, but it was certainly more than ten miles. By common consent none of us made it into a race, but our times were clocked in and we all had to make it within a time limit. Although capable of outstanding performances, Haydn always chose to jog along with me in the middle of the group. We were a very big field as all the courses in the O.C.T.U. ran together in this weekly test of endurance.

Haydn Tanner was a humble man, never trading on his physical prowess. He could, however, show righteous anger when roused by injustice of any kind. In one of the other courses was a group of five Canadians who constantly gave Haydn cause for annoyance. They were continuously making wisecracks at our expense. Rugby football was not one of their interests so they had no respect for Haydn’s prowess in this field. Neither they nor even the members of our own course knew of Haydn’s other qualifications. Prior to Officer training he had been a Sergeant-Instructor for P.T. at the Guards’ Training School at Caterham. I often heard him muttering under his breath at the comparative inexpertise betrayed by some of our own instructors for P.T. One of these usually led us on our cross-country, shouting disparaging remarks by way of encouragement. However, on one memorable day our P.T. Instructor announced that, as we knew the route so well, he was leaving us to find our own way round. When we were well on our way all the shouting was taken over by our Canadian allies. Coming to a side turning they announced that they were going to take a short cut and dared us “bums” to follow their example. We said not a word but plodded on in British silence.

Towards the end of our circuit the Canadians were waiting in mocking derision. Haydn immediately took charge and threw two of the Canadians into a very muddy ditch. The other three offered no resistance and they all obeyed Haydn’s command to follow him. He led them off to complete the route in the opposite direction. We gave them a rousing cheer and trotted back to camp. Haydn and the discomfitted, bedraggled Canadians ran in some fifty minutes later.

Haydn brought them home with an apology,

“Sorry to be late Sarge, but these benighted colonials couldn’t find the way, so I had to go to their rescue.”

They dared not speak the truth. Thereafter they treated the Brits with more respect.

There was one P.T.I., who instructed us in unarmed combat, who treated us “gentlemen” with profound contempt. He delighted in picking on individuals and making them objects of ridicule. He would demonstrate his skill by inviting attack and then throw his victim to the ground. One day the object was to creep up behind him and grasp him with a strangle-hold round his neck. The attacker would do his best, only to be thrown violently over the instructor’s head to land on the mat that had been mercifully placed. Two victims were thus humiliated, when the Instructor asked whether anyone else would like a go.

“Yes, I would like to try, Corporal.” said Haydn.

The challenge had to be accepted and the Corporal smiled in grim anticipation. Haydn’s fourteen stone went flying over his head, BUT he landed on his feet with his hand still holding the corporal’s collar. With this purchase he piloted the hapless instructor through the air to land helpless on the gym floor, well beyond the mat. Haydn was not a violent man, for he picked up the limp body and took him to be revived in the First Aid room.

No injuries were sustained and from that day the N.C.O. treated our course with profound respect.

CATTERICK CAMP

Life at Catterick was as hard as at Wrotham, but was more bearable. The pre-OCTU at Wrotham was purpose built and I doubt whether any trace of it remains. Catterick was the centre of Signals training and had been a camp since the days of the Romans. I can go through it today and recognise most of the buildings that we used during the War. I can even recognise the room where I slept for the whole nine months that I was there.

Today Catterick Camp is bigger than any of the towns around here. In the War it was even larger. There were well-built barracks with large dormitories where the floors were polished every day - by us! There were huge kitchens and dining rooms and N.A.A.F.I. canteens. There was a large hospital, cinema and theatre. In our Signals camp there were science labs, gymnasia, football fields, firing ranges, lecture rooms, parade grounds and vehicle workshops. In addition the Artillery, the R.A.F. and various other units had similar buildings.

Haydn Tanner was still my friend and his bed was next to mine. We had a lot of tests to pass, both written and practical. Some of these we had to do in pairs and Haydn was always my partner and, as a Cardiff science graduate, helped me to understand some rather obscure physics.

We had to pass all the trade tests for the different branches of signals work. Although we had passed in trucks and motor-cycles, we had to do a despatch riders’ and cable-layers’ exercise. We had to learn morse code and wireless signalling. We had to erect telegraph poles and climb them. We had to lay and join cables both overhead and underground. I have some photographs of us doing these things, I wonder whether you will be able to recognise me?

I think that you might have quite liked some of the more interesting things. For instance, in our practical tests we had to make a wireless set. In those days there were no transistors. We had to make what was known as a two-valve set. The power came from electricity or mains and the valves looked just like electric bulbs on top of the set. We had to use a diagram and get the necessary parts from the store. If the bulbs glowed, you could be certain that you had worked successfully, but the greatest thrill was to hear music coming through the head-phones.

We also had to make a morse transmitter and receiver. I think I still have the key somewhere. The night before the theory examination in magnetism and electricity Haydn took me through a two-hour session of question and answer. When the results were published, I was two places above him on the pass list. It just shows what a good teacher he was.

I think that I’d better keep the rest of my Catterick stories for another week. There’s still quite a lot to say.

November 2nd 1996

In my war-time stories to you I am spending a long time in Catterick. This is because we now live in that area and have continual reminders.

MORE CATTERICK CAMEOS

First of all, one or two Army words that you may not know. A “mess” is a place for eating. So we have the Officers’ Mess, the Sergeants’ Mess and the Other Ranks’ Mess. We all had two mess tins from which we normally ate together with an enamel mug and a “canteen” of knife, fork and two spoons. From this it follows that we all did our own washing-up: there was a swill bin in which went all our uneaten food, and two tubs of hot water in which we dipped our mess tins and cutlery before wiping them with cloths that were part of our equipment and which we had to launder.

Another word with a specialised meaning is “fatigue”, which applied to all those unpleasant extra jobs that had to be done from day to day.

The daily unfailing fatigues were those associated with the cookhouse, and were called by that name. In those days the most boring of these was “spud-bashing”, - peeling potatoes and preparing vegetables. There were no machines to help with these things. From what I have written above you will gather that washing-up was simplified, but there were still all the cooking pots and pans to do.

I managed to get out of a lot of these fatigues as I had been recruited into the entertainments squad by one Captain. K.D. Anderson who was a science master at Clifton College (note 15). He had seen me perform at the Bristol Little Theatre and the theatre manager at Catterick had been stage manager in Bristol at the same time. We used to rehearse during fatigue periods and I still have Captain Anderson’s book of the sketches that we did. These two officers, knowing my interest in the subject, also arranged for me to go with a load of old gas-masks to the storage dump then housed in the theatre at Richmond (note16). I can show you pictures of the place as it then was.

There are pictures of some of the tests we did at Catterick before we passed out as officers. There is also a picture of our passing-out parade.

There is one of three of us scaling a wall. The man who is being pulled up would stand with his back to the wall with his hands cupped. One at a time the other two would jump, and the man with his back to the wall would cup his hands under one foot of the jumper to give him a leg up. He, the jumper, would clutch at the top of the wall and pull himself up. When his two mates were thus secured at the top of the wall, they would pull the third man up. All this needed lots of practice. I mustn’t waste space describing other obstacles.

The supreme test of this nature was when we were all issued with individual rations and sent to do a battle course at Ullswater (note 17) in the Lake District. We had to wash in the Lake and rivers, from which we also obtained our drinking water. We cooked our own meals, when the mess tins were also used for cooking. The month was February and there was snow all around.

The most severe test of all was climbing Helvellyn (note 18), carrying a rifle and all our equipment. It was little comfort to see the ambulances following on the road below to rescue fallers and other casualties.

Back at Catterick we were taken out in lorries and dumped individually in the black darkness and ordered to find our way back to camp. We had the assistance of a compass with a luminous pointer. [Dad recalls that he was the first to make it back. He managed to flag down a car occupied by two ladies who, understandably, were initially alarmed at being waylaid by a stranger in full battle-dress. However, they kindly delivered him to the camp gates. He confessed the assistance he had received to the Sergeant on duty, and was half expecting to be sent out again. Happily he was instead praised for his enterprise.

For many years Dad has wondered why two lady civilians should have been motoring across a remote Yorkshire moor at 3 o’clock in the morning.]

We also did quite a lot of rifle practice. Some of us were not very good and a few sheep became war casualties. These sheep did their war service in the Camp Cookhouse.

All the time we were serving as ordinary soldiers, except for my first night, we never handled a rifle. As Officer Cadets we carried one every day. As Officers we were issued with revolvers for which we had no training. We were issued with four spare bullets and told to practice at home! I went into the orchard at Old Street Farm and aimed at a lone tree. I missed with all four shots.

All our section passed out successfully. Some of us had broken noses and broken limbs, but all refused to stay in hospital. We all knew that on release from hospital we would be returned to another section and this was a reduction in status that none could face. The interdependence and companionship was so very strong.

MUSTERED

After Catterick, Army life was certain to be something of an anti-climax. I have a picture of the passing-out parade. The Band of the Royal Signals was playing and marching in front, while the Princess Royal, Colonel-in-Chief of the Royal Signals, was taking the salute. The regimental march was “Begone Dull Care”, a jolly tune which Nick will probably be able to play for you.

We all went home on leave, wearing our brand new officer’s uniform and being saluted on all sides. For our dress uniforms we had been given a cash allowance and a supply of clothing coupons.

Looking back on things now, it seems that this was a big waste at a time when the Country could not afford it. These dress uniforms were not used until the fighting was all over and they took up a lot of room in the baggage that was more necessary. Four tailor’s shops were entirely devoted to this tailoring in Richmond, where there is now only one small gents’ clothing shop.

Haydn Tanner and I were posted to 12th Air Formation Signals. We were told that we should have to provide all the land communications for the 2nd Tactical Air Force [T.A.F.] that was formed to cover the invasion of N.W. Europe. We were assembled, or “mustered”, at a small place called Kirkburton, near Huddersfield. Of all periods in my Army life, this is the one about which I remember least.

In all there were sixteen hundred men in our total formation. We were divided into three companies for construction, maintenance and operational purposes. Haydn and I were to be in charge of 137 Line Section of No. 1, the Line Construction Company. We commanded sixty-five men. These included two sergeants, one corporal in charge of the Section Office, a vehicle mechanic, seven drivers, two officers’ batmen, a cook, and all the rest were linesmen. We were all Royal Signals, except the cook who was a member of the Catering Corps and did not parade with us on the rare occasions when this was called for. Our task was to build the short lines from the end of routes to the individual telephones and switchboards. We also had to lend men to the heavy construction sections when circumstances demanded. In operations it meant that I spent most of my time later at R.A.F. headquarters.

At Kirkburton men assembled from many different places. The Junior Officers nearly all came from the course at Catterick. The Senior Field Officers were older territorial reservists who occupied responsible positions in the Post Office. At that time there was no British Telecom and all telephone engineering was done by the Post Office. It was natural that, not only officers, but most other ranks came to us straight from the Post Office. Similarly some came from the electricity companies as the skills of line building are similar. We had to give them some rough guidance about Army drills and signal equipment.

Now comes the only story that you are likely to appreciate in this week’s history lesson.

As well as men, equipment was also coming to us in regular deliveries. One day we were informed that motor-cycles for our despatch riders had been sent to Huddersfield railway station. So far we had no trained despatch riders, but an all-providing War Office had arranged that 25 professional riders would be coming to us straight form civvy street.

I cannot remember exactly how the Unit orders were phrased, but there was information that motor vehicle equipment was awaiting collection at Huddersfield railway station. On the following day two three-ton lorries would proceed to collect the stores and sign for same. The Officer in Charge would be 2nd/Lieut. F.C. Willmott. He would also be responsible for collecting 26 motor-cycles and meeting the new recruit motor-cyclists who had been directed to the station on that day. They would ride in ordered convoy to the camp at Kirkburton. The operation would be commanded by the Officer in Charge for whom an additional motor-cycle had been ordered.

I regarded the prospect of this military operation with much trepidation. You may remember that my motor-cycling had not been the brightest spot in my training. I still bear the scars.

When we reached the station the motor-cyclists, still in civilian clothes, had already selected their machines and were ready to start. The remaining machine was obviously the outcast of the batch. Wisely, I decided to copy The Duke of Plaza-Toro (note 19) and lead my regiment from behind. I lined the riders in double file and they revved up, raring to go. When I kick-started my machine there was no response. Helped by one of the professionals the engine coughed into action and we poured forth into the unsuspecting traffic of Huddersfield. My bike also had a faulty exhaust and kept up a continuous rattle of imitation machine-gun fire. At every road end and turning the convoy waited for me, moving off again before my engine stalled. These men were very good sports and saw my problems sympathetically. On arrival at the camp they separated files, allowing me to pass through to head the column with all exhaust guns blazing. From that day I have never again ridden a motor-cycle.

The only other memory I have of this stay at Kirkburton concerned Haydn Tanner. At that time Keighley had a good Rugby League side, with miners exempt from military service. They also had their scouts looking to snap up any military personnel in the area who might also play professional rugby. Their scouts found Haydn, who was invited to meet the directors at their next home match. Haydn asked me to go along with him. He had no intention of signing, but said we should get a jolly good meal with vintage wine. We sat in the Directors’ Box to watch the game against Featherstone Rovers, and the refreshment was lavish. They offered Haydn a cash advance on the spot, but he said he would let them know.

They also said that they would be glad to see me as well, but I wasn’t offered any money.

UNDER STARTER’S ORDERS

Thirsk has a splendid race-course. Today the small town is also well known as the place where James Herriot had his vet’s surgery. Less well known is the small cricket museum at the house where Thomas Lord lived before taking his Yorkshire turf to make a world famous cricket pitch in St. John’s Wood in London.

In 1943 there was no cricket at Lords, James Herriot, not yet a writer, was in the Air Force and there was no horse racing at Thirsk.

Our 12th Air Formation Signals moved into the ample accommodation usually occupied by horses. We made up half the wartime population of the town. At Kirkburton we had been cramped and were not able to unload and test the supplies that had been delivered, or exercise the sixteen hundred men that had been assembled. In addition to my official command of 137 Line Section, I had been listed as Unit Entertainments Officer. To offset the men’s boredom I was kept very busy, and we were lucky that there were a number of amateur concert parties in the area very willing to visit us. We also formed our own party that I directed. Fortunately we had one Signalman Marshall, a brilliant pianist, who could play anything with, or without, sheet music. I never saw him do any routine work, and I never saw him in need of buying a drink.

The situation changed completely when we moved to Thirsk: for one thing it was summer time and there was plenty of room to do the work and training that we needed. The teleprinters, switchboards, telephone poles and cables came out of their packing to be tested, adjusted and used. All the vehicles needed attention and we had to learn how to waterproof the engines so that the vehicles could be driven off the landing barges on the French beaches later on.

There was plenty of room for other exercise and activities that bordered on training. As far as petrol rationing would allow the motor-cyclists did trick riding and racing round the circuit that usually saw horses. There were tugs-of-war between our various sections and team races carrying telegraph poles. The public address system and all the race-course telephone lines were renewed and extended. We did all the grass cutting and serviced the buildings we were using. This was all in our interest as we were very comfortably housed. I lived in a stable usually occupied by horses overnight during the racing season. The local people were all very hospitable and invited us to their houses. We were rather spoilt as we were the only service unit in the area. Families and girl friends came up for weekends. Grandma came up with Lorna and Rod to stay for the night at a Mrs. Lane-Fox’s.

During this period our commanding officer and two of our three company commanders were replaced. We don’t know why they were sacked, but the replacements were much more dynamic and seemed to have been trained for the task ahead. Probably their predecessors had been recruited for home service and had completed the routine job that they had to do.

So far this has been poor factual stuff, but now comes the only interesting story from this period.

Our new Commanding Officer, Lt.-- Col. Tom Norrish, was very good at public relations. He had the great idea that we should do something to repay the hospitality of local people.

As Entertainments Officer I was expected to do something about this. Obviously we were in a good position to provide an outdoor entertainment if a suitable programme could be devised. The race-course stands could provide ample seating accommodation for the whole civilian population. We could build a stage in the race-course arena and we had already perfected the sound amplification equipment. However, I doubted whether we had the resources to provide suitable musical entertainment. We were quite good in the canteen or the pub smoking room, but hardly fit to fill the needs of a vast outdoor auditorium. We had the inspiration to appeal for help from the Royal Signals Band.

We were pleased to find that they were very willing and well-equipped to feature on such an occasion. They had a programme for a marching band, a concert section, and a dance band, with popular vocalists. We only had to hire a well-tuned piano in addition to the staging we had already planned.

There only remained the problem of a suitable date and transport. The Band, with its load of valuable instruments, usually travelled by rail. Fortunately we were very near to Thirsk station so this should make things easy. The only snag was that very few trains stopped there, though there was plenty of traffic between York and places further North. We were able to find a date when the Band were playing in York on the previous evening. They could be ready for a Concert at Thirsk at 2.30pm on the following day.

At that time Thirsk railway station was manned by a very elderly station-master, assisted by a lady porter and a young girl booking-clerk. They were all very good friends. They assured me that they could arrange for any train to stop at their station; particularly when meeting military requirements.

Under this arrangement the Band would be ready to start after a speech by the Colonel and an exhibition of skills by some of our linesmen and despatch riders. These were the very professionals whom I met at Huddersfield. I missed their turn as I was waiting at the station. I understand that their display of acrobatic riding was superb.

Right on time the bandsmen arrived at Thirsk and we waved to them; only to see them go right through the station at speed. All the arrangements had been made, but nobody told the driver. However, all was not lost. Phone calls were made down the line and the Band got off at Northallerton. They were put on the next train coming back to York. This time the engine braked and appeared to be stopping; but no. Everybody waved and shouted, but the train didn’t stop until the driver got the message - some way beyond the station. He reversed and all was well; nearly! The driver started off again before the larger instruments had been unloaded from the Guard’s van. Another reverse, and eventually we reached the race-course nearly an hour late. Nobody grumbled and, finally, a programme that started at 2.00pm ended at 5.30pm.

December 1st 1996

... My story has been extra long this week, and even so I’ve left out some bits. Grandma says that the family stayed more than one night in Thirsk. Rod distinguished himself in the bathroom by pulling a forbidden chain and causing an endless flow of water, only stemmed by one of my skilled soldiers ...

WINGED MERCURY

The Royal Signals badge is a figure of Mercury, messenger of the Gods. As members of the 12th Air Formation Signals we also wore blue shoulder flashes featuring R.A.F. wings. Up to the time of leaving Thirsk we had no contact with the Air Force. When we moved south to take up pre-invasion positions this situation was to change completely.

The Headquarters of the 2nd Tactical Air Force was by Uxbridge and the Rear Headquarters was at Bracknell. These were quite separate from Bomber and Fighter Commands. Their line communications were all permanently constructed long before our arrival, but we took over the lines and equipment with the task of maintenance and building extensions. We worked at the two sites, but we were accommodated at Whetstone in North London. We lived mainly in evacuated households or in similarly empty school buildings. We became acquainted with the R.A.F. staff, but the work load was not heavy. Consequently my spare time work as Entertainments Officer became more important. As in Thirsk we had excellent relations with the locals, but we were discouraged from joining the crowds of central London in the evenings. In any case we were in a part of greater London that was almost untouched by bombing.

During this period we formed a Dance Band as well as our Concert Group. Instead of amateur entertainers visiting us, we served the local bodies by providing their shows and dance music. These were the circumstances that led to this week’s story.

In the road where I was billeted lived a local businessman who gave me an open invitation to his house and was very kind to me. His name was Mr. J. Foley and he was a high executive in the management of the Gas Company. I can’t remember what it was called in those days. Everything in his house operated on gas and there was no electricity. Even his radio and gramophone worked on gas. You may wonder how this could be possible, but your Dad and Mum will be able to explain to you how one form of energy can be converted to another. For example, some electricity is manufactured by using windmills. In the case of the radio it was gas that heated chemicals that charged a battery providing the power for the radio. All his gas lights operated by using an ordinary wall switch.

Mr. Foley was also a local Councillor and Chairman of the local War Savings Committee. Again your parents will explain what this meant. You must remember that the War cost a lot of lives, and a lot of money.

Mr. Foley had a lot of contacts in the entertainment world and he was quite a fan of our Dance Band, and also of the Dance Group of girls from the near-by gun-site. So it came about that we organised a Concert, of which I have been able to find the programme.

[Programme for Friern Barnet “Salute the Soldier” Concert, British Restaurant, March 25th]

I see that I am listed as Stage Manager, but this was combined with one or two stage appearances. Our group devised and performed the various sketches in the programme.

Just one or two words of explanation. You may wonder what was a British Restaurant? In most towns these were opened in public halls and mid-day meals were sold at a very reasonable rate. They were not lavish, but were very welcome when most people were working and everything edible was rationed. It was hoped that these social eating centres would continue well after the War, but they did not survive long after rationing was ended. When we moved to Leeds one of these restaurants still survived in the basement of the Town Hall, but I doubt whether your Dad can remember it. The one at Friern Barnet was large and had a good stage, but all the curtains had been removed for the greater convenience of the restaurant.

You will see from the programme that there were some star performers whose names are in heavy type. There were two performers at the piano famous as Flotsam and Jetsam. One of them lived in the locality and is billed as Mr. Jetsam. His real name was Malcolm McEachern (note 20).

Webster Booth and Anne Ziegler (note 21) were appearing in London’s West End at the time. Because of the danger of air-raids all the London theatres opened and closed very early in the evening. The two star artistes came on to us after their West End performance. To our delight and surprise they came with all their stage clothes and sang their current numbers.

I did not foresee that I might be involved in their Act.

My batman-driver, Norman Reed, was a Londoner by birth and business. He volunteered to fetch our star artistes from the theatre. He had been a London taxi-driver and held a cabby’s licence. He was able to borrow a cab from one of his friends and duly waited at the Stage Door in Town. As soon as the curtain was down on the show the stars emerged resplendent in their costumes. Anne Ziegler’s dress had a long train that was borne to the cab by a stage hand and carefully draped inside. At the Hall she would not get out of the cab until someone could come and carry her train. That was the point at which I came into the Act.

I was dressed as smartly as possible in Army dress uniform with my Sam Browne belt. Webster Booth was arrayed in a much more colourful military dress, with rows of medals and high cocked hat. We went into the Hall through an entrance to the suite of rooms behind the stage. My batman led the way and I brought up the rear holding the lady’s train well off the ground, in obedience to her instructions. Although a star, she was obviously in awe of the wardrobe mistress who had objected to the costumes going out of the theatre. So I followed Miss Ziegler everywhere, even to the ladies toilets, standing uncomfortably outside the cubicle door, waiting to be handed the train.

When the Booths made their entrance from the door at the back of the stage there was a tremendous ovation, to be followed by laughter and a cheer when I followed meekly as train-bearer. Webster Booth gave me his white gloves and dismissed me with an imperious gesture.

At the end of the Act I had to come on again, so I handed back the gloves with a bow. In the meantime I had borrowed Reed’s huge gauntlet gloves and concealed them in my capacious pockets. I produced these and put them on before delicately picking up the fringe of Anne Ziegler’s train with the tips of the fingers. Rolling my hips in imitation of Miss Ziegler we all made a triumphant exit.

A “STAR” TO STEER HER BY

The big concert recorded in my last story was our last event before we set off for Normandy.

I can’t remember whether I told you that Haydn Tanner was sent back to Catterick as an instructor during this period and was replaced by young Dickie Claydon, an energetic performer on the motor-cycle. I got on with him very well, but never as closely as I did with Haydn. He was, however, very suited to the roving commission to which he was assigned in operations.

Once D-Day arrived we had to be ready to set out at an hour’s notice. It was about twenty days before that order came.

Now comes a boring bit. From the days of the Romans and the Normans armies had crossed the Channel in landing craft and waded ashore on the other side. These soldiers, like the Angles and Saxons, carried their weapons with them. In 1944 there were also tanks and armoured vehicles that had been built to plough through water and obstacles while shielded from enemy fire. We had a lot of heavy vehicles full of expensive telephone equipment that depended on temporary water-proofing. We relied on optimum conditions of tide, weather and defensive cover to get across safely. At this time there was also the factor that the German second line of defence was holding well, so there was a heavy build-up of allied troops in the Normandy bridge-head. Encamped under canvas along the sea-shore these soldiers also faced the problem of boredom. This is where my story has its place.

As we received our final orders for embarkation I was sent for by our commanding officer, Lt.-Col. Tom Norrish. He had been informed that there was a desperate need for entertainment on the other side of the Channel. Resources could not be spared to send ENSA (note 22) parties over, but individual artists could be smuggled over if Entertainment Officers were prepared to take the risk. It was emphasised that I could not be ordered to do this, but that it would be credited as a praiseworthy contribution to the War Effort. How could I refuse?

I was sworn to secrecy and was not told the name of the entertainer who would travel with me in my jeep. I just had to make room for him and his baggage. Should I recognise him, I must keep the identity to myself as his identity might breach security. I was given a map reference in Hampshire where my passenger would await me in uniform and under escort.

The next day we were on our way and, although we were behind schedule, there was obvious activity at the appointed place. In fact there was quite a crowd and the identity of our pick-up was no longer secret. It was George Formby.

If you look at his picture you can see that his features are quite remarkable. What surprised and worried me was that his wife, Beryl, was also with him and similarly uniformed and equipped for active service. There was no time for discussion as we were travelling in a big convoy and the identity of our passengers was quickly spreading all along the line. Somehow George and Beryl were bundled in and we set off for our point of embarkation.

When we arrived somewhere near the coast our convoy was in procession behind others, all lining up to board our vehicle landing craft. Of course it was all very secret and we were not supposed to know where we were, but our bet was that we were in a back street of Southampton. We were told to get what sleep we could as we should be sailing just before morning light.

Uncomfortable inside our jeep, George got out and, scarcely incognito, he brought out his ukelele (note 23) and entertained all and sundry. He was, literally, leaning on a lamp-post at the corner of the street. The problem of George and Beryl’s overnight accommodation was more than readily solved by willing householders alongside.

We embarked very early and in the early morning light got ready to drive ashore at Arromanches. The scenery looked familiar and, ready for anything, we found we were back in Southampton: for some reason we had been turned back in mid-channel. So we and the citizens of Southampton had a second night of entertainment. Eventually we reached the French coast and we were grateful that our water-proofing stood up to the test. We set foot on the beach without getting our boots wet. I handed over the Formbys to an escort of military police amid mutual thanks.

That’s the end of this little story. However there are other points of mutual interest.

When I was in Bristol on holiday as a small boy, I was taken on my first theatre visit: a Music Hall. Top of the bill was George Formby, father of the one about whom I have been writing.

When I began teaching, Jim Harvey and I went into lodgings at Mrs. Keyes, near Redland Station (note 24). Her daughter, Lillian, was a well known singer and did the female vocals for young George Formby’s film, “Boots” (note 25). I remember how proud her father and mother were. This was the time that George had emerged as a pop star as famous as Gracie Fields.

Grandma’s brother, Uncle Bill, became a great fan. When he stayed with us in Frome we sent him as a responsible teenager to see an early evening showing of a George Formby film. When he had not returned by 10.00pm we became quite worried and set out in search. We met him on his way back, still laughing after seeing the programme through twice.

It was after we came to West Witton that I discovered that the young George Formby had been a stable boy at Middleham, having been apprenticed as a jockey. Several locals whom I met when lecturing on the Music Hall had their own personal memories. He often visited the farm house that you pass on your way up Penhill and did his early entertaining in the local Inns here. Dr. Anderson, who was for many years Chairman of the local Tournament of Song, told me that George competed both in 1913 and 1914.

So much for the unrecorded facts of history. More important is that George Formby was the first ENSA recruit to take part in the Normandy invasion. I thought that Beryl Formby might have been the first woman to go over, but there were some nursing Sisters who went over very early on.

George and Beryl Formby with F.-M. Montgomery

George and Beryl Formby with F.-M. MontgomeryVIA VAUBADON

After we had handed over the Formbys to the military police at Arromanches we were given our instructions by the Beach Marshall. He gave us a summary of recent developments in the area and a caution that there were still pockets of enemy resistance. We were warned particularly about the intrusion of individual snipers who had inflicted casualties before getting well away into a countryside with which they had made themselves very familiar, and where there were a few French collaborators.

My Section was directed to encamp at a farm near Vaubadon (note 26). I have never tried to find the place on the map, but it must be somewhere near Bayeux. We put up the bell tents in a large ploughed field, but I had the seclusion of a pleasant orchard for my individual canvas top. We had been in our vehicles for three days and nights, so the comfort of a camp bed was a real luxury.

I was awakened from a deep sleep by the sounds of heavy breathing and of somebody moving round my tent. I slipped quietly into my battledress and loaded my revolver. Holding this at the ready I crawled out and round the tent. I was met by two large staring eyes and a snort before a cow galloped away into the darkness, dragging away my tent having tangled her hoof in the guy-ropes. I couldn’t show a light so it was impossible to rebuild the tent. I slept the rest of the night wrapped in my martial cloak (note 27) - and canvas.

In that congested countryside the days that followed were not very exciting. Although generally welcomed by the locals, I sometimes wondered whether we were a greater burden to them than the Germans had been. Occasional road incidents prompted such reflections. There was the occasion when one of our drivers came to me in great anxiety. He had had an accident involving a small boy from a neighbouring farm. Our men had done their best to meet the family and had assured themselves that no serious bodily harm had been suffered. However, the family had been most belligerent and one of the men had offered physical violence.

We had been given strict instructions on dealing with native populations and I realised that I had a duty to do something about this. I had studied my French phrase book and set out with driver Reed to make our overtures.

The family were still in hostile mood, but softened when I spoke my first words of well-rehearsed French. “Ah, vous parlez Français?” I was immediately invited inside and did my best to continue without speaking a word of English. Sadly, at this time I was a smoker; but not an addict. I handed over my accumulated cigarette ration, an incomparable luxury in that region at that time. Out came the coffee and an unknown poison called calvados (note 28). This was served in very small glasses and I observed that the men drank the contents in one draught before an immediate refill.

I did the same; and thought that I should explode. Conversation became very lively and I drew upon wells of A-level French that had languished long in the subconscious. When I walked out my feet were not aware of any floor. Fortunately Reed, entertaining the ladies and the children in the kitchen, had remained very sober, but had parted with all his sweet and chocolate ration. By way of compensation he had an odorous supply of Camembert cheese. The success of my mediation gained me a reputation that made me official interpreter in both France and Belgium.

These stories were but two of the day-to-day happenings of a very boring period. More important events were to follow, but I am certain that the events here recorded are not in any official history. They are set down on paper here for the very first time.

News came that the blockade had been broken and that, operationally, we should soon be on the move. Accordingly our line-laying equipment and linesmen were deployed in the probable direction of advance and my section camp was deserted. My fellow officer, Dickie Claydon, stayed out with the men and I returned to my lonely tent to await instructions.

I was about to retire to my camp bed when there was an imperious ring on the field telephone. It was Colonel Norrish; he was in a state. Field-Marshall Montgomery was in a rage. He had just discovered that he could only speak to the R.A.F. commander, Air Vice Marshall Coningham, by going through our switchboard. He ordered that a one-to-one line be laid immediately. I was the only company linesman within call: with the assistance of my own and Dickie Claydon’s batmen, I had to lay the line.

The operation was familiar to me from Catterick days, but our batmen had no such training. Norman Reed was a most efficient practical man, but Claydon’s batman, XXXX, was an affable but verbose Welshman, very willing but accident prone. Roused from his bed, he couldn’t find his false teeth, so he was mercifully silent on this occasion.